ARCHIVED CONTENT

This content is no longer being updated.

The foreign financial sources behind Indonesia’s unnecessary coal expansion

The finance behind Indonesia’s plans to build up to 31 gigawatts of new coal power capacity is overwhelmingly from foreign sources, most notably China, Japan and Korea. Public institutions such as export credit agencies play a critical role in de-risking coal power projects. They shoulder a significant burden of the credit exposure for new Indonesian coal power stations to the point where such projects would be unlikely to proceed without foreign government-backed finance.

Summary:

- This analysis reviewed deals comprising debt finance to 21 coal power projects with a combined capacity of 13.1GW, which reached financial close from January 2010 to March 2017.

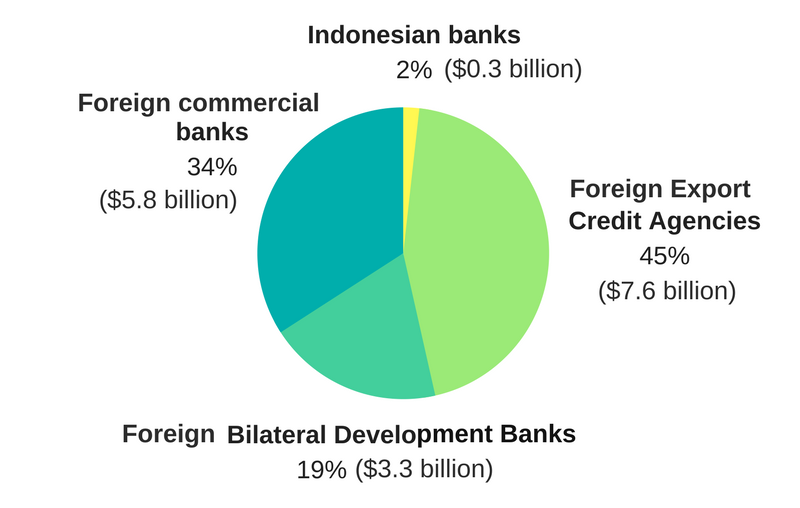

- Export Credit Agencies participated in 64% of deals and loaned 45% of total debt.

- Bilateral Development Banks participated in 27% of deals, lending 19% of overall debt.

- The power plants studies were majority foreign owned. 51% of the overall project value was owned by Japanese and Chinese companies, with 39% Indonesian-owned.

- Indonesia bears much of the financial, environmental and health risk associated with these new plants, many of which will exacerbate oversupply of the electricity networks in which they’re to be integrated.

China, Japan and Korea are constraining domestic plans to expand coal power. As a result, export markets for plant manufacturers are becoming increasingly important. Indonesia’s coal expansion plans present an opportunity for foreign manufacturers producers, able to mobilise public finance sources to facilitate the export of their technology.

The result is an expansion of polluting power that benefits a handful of domestic and foreign interests, while putting the health and livelihoods of communities at risk. Constructing these new power stations would also contribute to an anticipated oversupply of power in Indonesia, further undermining their justification.

Public finance plays a critical role

Market Forces studied a total of 22 deals to the coal power sector in Indonesia since 2010, which attracted a total of US$17.1 billion of debt. Of these, Export Credit Agencies (ECAs) and Bilateral Development Banks were integral financiers, involved in 91% of the deals and providing 64% of the debt finance.

Specifically, regarding the roles of ECAs, Bilateral Development Banks and commercial banks:

- ECAs were involved in 14 of 22 deals, lending $7.64 billion

- Almost all of this debt (99.6%) was provided by overseas ECAs

- Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) was involved in 5 deals, providing 64% of ECA lending

- The Export-Import Bank of China (CEXIM) was involved in 7 deals, representing 31% of ECA loans

- Bilateral Development Banks were involved in 6 deals, lending $3.30 billion

- China Development Bank was involved in 5 deals, lending 93% of Bilateral Development Bank debt

- Korea Development Bank participated in 1 deal, providing 7% of Bilateral Development Bank debt

- Commercial banks were involved in 13 deals, providing $6.14 billion

- 95% of commercial debt was provided from banks outside of Indonesia

- 57% of commercial debt was provided by Japanese banks over 7 deals

- 14% of commercial debt was provided by Chinese banks over 4 deals

- 10% of commercial debt was provided by Singaporean banks over 5 deals

Indonesia’s share of lending to these deals was exceedingly small, accounting for just $347 million or 2% of overall debt over 2 deals. One of these deals involved Indonesia Eximbank and the other involved Bank Mandiri.

| Total | ECA / Bilateral Development Bank involvement | |

| No. coal power deals | 22 | 91% (20 deals) |

| Total lending value | $17.1 billion | 64% ($10.9 billion) |

Table: Number of coal deals and value of debt identified in this study, with involvement of export credit agencies (ECA) and Bilateral Development Banks highlighted.

Finance sources for Indonesian coal power January 2010 – March 2017

Foreign ownership + foreign engineers = foreign finance

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>The overwhelming proportion of finance coming from sources foreign to Indonesia is a product of the power stations being predominantly owned by non-Indonesian countries, and almost exclusively built by engineering contractors from outside of Indonesia. </span>

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Of the 13.1GW of coal power capacity covered by this analysis, 51% was owned by Japanese and Chinese companies, with 39% Indonesian ownership. Indonesia’s state-owned utility PLN had an overall ownership stake in the projects studied of 15%, with other Indonesian companies owning 24%.</span>

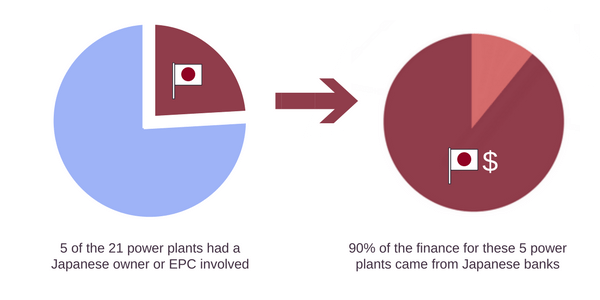

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Of the 4 power projects involving Japanese sponsors, all attracted Japanese ECA guarantees and loans. Japanese engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractors were involved in 3 of these projects. Japanese EPCs were involved in 4 power projects in total, including one sponsored by Indonesia’s PLN.</span>

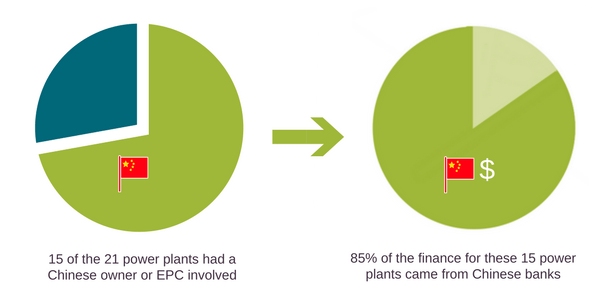

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Of the 7 power projects backed by Chinese sponsors, 6 attracted loans from Chinese public finance institutions, 4 attracted Chinese commercial lending and all attracted lending from either one or the other (or both). At least 5 of these 7 projects involved Chinese EPCs, whilst the identity of the EPCs was unclear for the remaining 2. Chinese EPCs were prevalent, involved in 13 of the 21 coal power projects studied.</span>

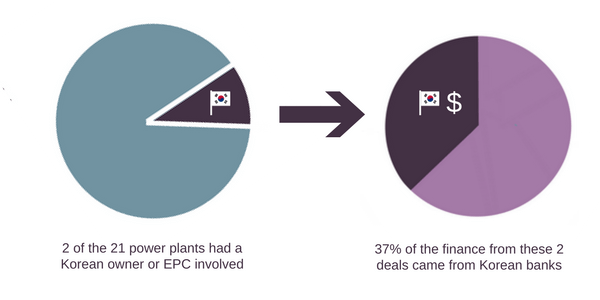

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>4 of the 21 power projects studied had no Chinese or Japanese EPC involvement. 2 involved Korean EPCs and 2 involved Indonesian EPCs (<a href=”http://www.dcengineering.asia/dnc-new/index.php?about”>one of these Indonesian EPCs partners with a Chinese EPC for technical support</a></span><span style=”font-weight: 400;”>). Another 2 plants employed unknown EPCs, though it’s suspected these were Chinese as both were sponsored by Chinese companies and attracted all known finance from Chinese banks.</span>

<span style=”font-weight: 400;”>Foreign commercial banks tend to play the role of completing a syndicate that is largely de-risked and underwritten by the ECA of the same country. Of the 11 coal power deals with both commercial and public bank lending, 9 involved commercial and public banks from the same country. Only 2 coal power deals attracted debt exclusively from commercial banks, with one of these deals being a bridge loan.</span>

Greater imperative for China, Japan and Korea to build coal power overseas

The prospects for new build coal power in Korea, Japan and China are limited, as rapidly falling costs of renewable energy, efforts to reduce air pollution, and climate change policy all reduce demand for coal plant technology.

In China, the rise of renewable energy and pollution concerns saw coal consumption fall for a third consecutive year past peak use in 2013. China plans to cap coal consumption in 2020, peak its CO2 emissions by 2030 and invest US$361 billion in renewables by 2020. Japan has seen energy efficiency drive down electricity demand over the past 6 years and further declines will likely result in a scaling back of plans to construct a new coal power fleet. Further, the country is positioned to meet 35% of electricity needs with renewables by 2030. In Korea, coal generates 40% of electricity but this appears set to decline after president Moon Jae-in announced the temporary closure of 10 plants, following campaign pledges to shut old plants, review additions and increase the country’s share of renewables.

With opportunities becoming limited in their host countries, Japanese, Korean and Chinese manufacturers are looking for opportunities elsewhere, as is evidenced by statements from analysts and government:

“Asian and Eastern European countries will introduce coal thermal plants — no question about it. We cannot stop it. Then who will supply coal thermal technology to them? We can’t make all countries stop using coal… because coal is very cheap.” – Toshikazu Okuya, Director, Energy Supply and Demand Policy Office, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (Japan).

Export Credit Agencies and Development Banks deliver on this agenda by financing Indonesian coal projects that: (i) employ EPC services (i.e. building plants) from the relevant foreign country; and/or (ii) are owned by companies domiciled in the foreign country.

ECAs provide loans, guarantees and/or insurance, which facilitates the purchase of exported coal technology from, for example, Japan via JBIC or China via CEXIM. Development Banks provide finance to the private sector for economic development and are only able to finance projects that support their national agenda.

China and Japan bankrolling projects: Examples

Below are two examples of plants in Indonesia owned and funded by Japanese and Chinese companies, demonstrating how the owner-operator-financier arrangement applies.

TJB2 (Japan)

The 2,000MW Tanjung Jati B 2 (TJB2) coal power expansion in Central Java reached financial close in March 2017. It is 75% owned by Japanese companies Sumitomo Corp (50%), who is also the EPC contractor, and Kansai Electric Power Co. (25%). The deal attracted US$3.36 billion of debt finance, half of which was provided by JBIC. The other half was provided by 7 commercial banks, 6 of which are Japanese. The commercial debt was guaranteed by the Japanese ECA Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), which provided 100% political and 90% commercial risk cover.

Jawa-7 (China)

The 2,000MW Jawa-7 coal power station reached financial close in September 2016. It is 70% owned by China Shenhua Energy and 30% by PT Pembangkitan Jawa Bali (a subsidiary of the Indonesian state-owned electric utility PLN). The identity of the EPC is unclear despite reports that construction commenced in April 2016. Given the majority owner and all known finance came from China, it is likely the EPC is also Chinese. The project attracted US$1.8 billion in loans from an all-Chinese banking syndicate led by China Development Bank (also reported here).

Banking without a permit: Cirebon 2

The detachment between interests within Indonesia and foreign financiers was made even more apparent in April 2017, as ECAs JBIC, KEXIM and NEXI signed financing agreements for the 1,000MW Cirebon 2 coal-fired power station in Central Java, a region for which there is a projected oversupply of power. The deal was inked despite a verdict from the Bandung administrative court being due the next day (19 April) pertaining to the environmental status of the project. The court case, filed by The People for Environmental Protection (RAPEL), assisted by the Advocacy Team for Climate Justice in December 2016, resulted in the revocation of Cirebon 2’s environmental permit.

The detachment between interests within Indonesia and foreign financiers was made even more apparent in April 2017, as ECAs JBIC, KEXIM and NEXI signed financing agreements for the 1,000MW Cirebon 2 coal-fired power station in Central Java, a region for which there is a projected oversupply of power. The deal was inked despite a verdict from the Bandung administrative court being due the next day (19 April) pertaining to the environmental status of the project. The court case, filed by The People for Environmental Protection (RAPEL), assisted by the Advocacy Team for Climate Justice in December 2016, resulted in the revocation of Cirebon 2’s environmental permit.

At best, the banks involved in the deal were ignorant of this critical development in a project they were involved in financing. IJGlobal reported the reaction of a lawyer working on the finance deal who:

‘…was not aware of this case, and was shocked to hear about the news, especially a day after the plant reached financial close.’

However, it is likely the banks and their staff involved in this deal knew of the risk that the project would lose its environmental permit. The financing agreements therefore appear contemptuous towards the groups attempting to protect their environment from Cirebon 2. The fact that the banks shifted the signing date to the day before the verdict was handed down emphasises this contempt.

Wahyu Widianto, campaign manager of WALHI West Java said:

Indonesian pain for China, Japan and Korea’s gain

Despite the limited prospect of financial returns and limited employment creation in engineering and manufacturing, Indonesia bears a significant burden of the isolated and systemic financial risks of the new coal power stations, along with the environmental and health risks they pose.

For example, although Indonesia owns just over one-third of the 13.1 GW of coal power capacity studied, 100% of the greenhouse gas emissions will be accounted for as part of Indonesia’s national inventory. These emissions are estimated to total in excess of 2.2 billion tonnes of CO2 over the power plants’ operating lives, equivalent to the annual CO2 emissions of India (2.45 billion tonnes). This figure does not include the Cirebon 2 project, which has not reached financial close but for which financing documents have been signed. Adding the emissions from Cirebon 2 would increase the total from this study by a further 165 million tonnes of CO2.

Regardless of which country is ultimately accountable for the emissions, plans to massively expand coal power are at odds with the Paris Climate Change Agreement, which aims to limit global warming to well below two degrees. According to John Roome, Senior Director for Climate Change at the World Bank, “If all of the business-as-usual coal-fired power plants in India, China, Vietnam and Indonesia all came online that would take up a very significant part – in fact almost all – of the carbon budget… It would make it highly unlikely that we would be able to get to 2°C.”

New coal, not necessary

At present Indonesia has 55 GW of installed electricity generation capacity, 56% (31 GW) of which is coal. Indonesia plans to expand total capacity to 125 GW by 2025 with coal accounting for 50% (or 62.5 GW). But the availability of other power supply options, and an oversupply of electricity in many areas where new power plants are proposed undermine the argument for constructing new coal.

Analysis of Indonesia’s latest Electricity Supply Business Plan, named RUPTL 2017-2026, shows that current power expansion plans would result in significant oversupply across a number of Indonesia’s electricity networks. Specifically, plans would see grid reserve margins across Sumatra, Java-Bali and Kalimantan of an average 60% in 2021 and 59% in 2026. For example, projected peak load in North Sumatra in 2021 is 3,786 MW compared to 7,238 MW of capacity (91% margin), whilst in Java-Bali peak load is projected at 35,722 MW compared with 51,800 MW capacity (45% margin).

In April 2017 Ignasius Jonan, Minister for Energy and Mineral Resources, stated that assuming economic growth of 6%, construction plans are expected to see Java-Bali have excess installed capacity of 5 GW by 2021. Jonan has stated he will not sign power purchase agreements for Java-Bali moving forward, resulting in the indefinite postponement of 9 GW of planned capacity.

Indonesia can meet its future energy needs through renewables. The 2017-2026 RUPTL raised the country’s renewable energy target to 22.5% of electricity supplied by 2025 from a previous 19.6%, demonstrating a willingness and ability to increase the country’s renewables capacity. Further, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) “Indonesia could feasibly exceed its current goals and deploy even more renewables. In fact, the country could reach its 2050 target two decades sooner – by 2030.”

Methodology

Market Forces examined 22 financial deals comprising a debt component, across 21 coal power projects, with a financial close date from 1 January 2010 onward, expressly for the development of coal-fired power stations in Indonesia. The most recent deal included in this research reached financial close in March 2017.

The full list of coal power finance deals included in this study is available here.

Deals were identified via investigation of subscription-based financial databases provided by IJGlobal and Thomson Reuters and reports published by organisations including:

- Climate Policy Institute (CPI)

- Environmental Defense Fund (EDF)

- Graduate School of Public Policy (GraSPP) at the University of Tokyo

- Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC)

- Sourcewatch (The Center for Media and Democracy)

- Company reports and media releases

Where financial information was identified, it was cross-referenced with the sources listed above, media reports and other financial journals. Where material information between sources was inconsistent or unavailable, a determination was made to attempt to reflect the true state of the deal.

Lending for the purposes of refinancing existing debt, corporate acquisitions, or acquisitions of existing assets were excluded from the study. Where the source of funds was unknown, lending was excluded. All lending amounts are reported in US Dollars (USD) unless stated otherwise. Lending amounts are as at the date of financial close and aggregated figures were reached by adding these amounts.