Market Forces in the media

Originally published in RenewEconomy, 13 October 2014

A lot has changed in the last few years. Just a few years ago, with prices of both thermal and coking coal through the roof, it was cigars and caviar time for an industry who were proposing more new projects than you could point an activist at. A long and glorious future was expected, based on China’s insatiable demand for coal – our coal.

It didn’t quite work out that way. A slight drop in GDP growth in China saw coal piling up in import stockyards. Then, the recognition that China’s horrendous air pollution problem needed urgent action has seen all manner of restrictions and caps on future coal consumption. And all the while, that other world leader in carbon pollution – the United States – continued to close coal power stations as gas, renewable energy and efficiency plugged the gap.

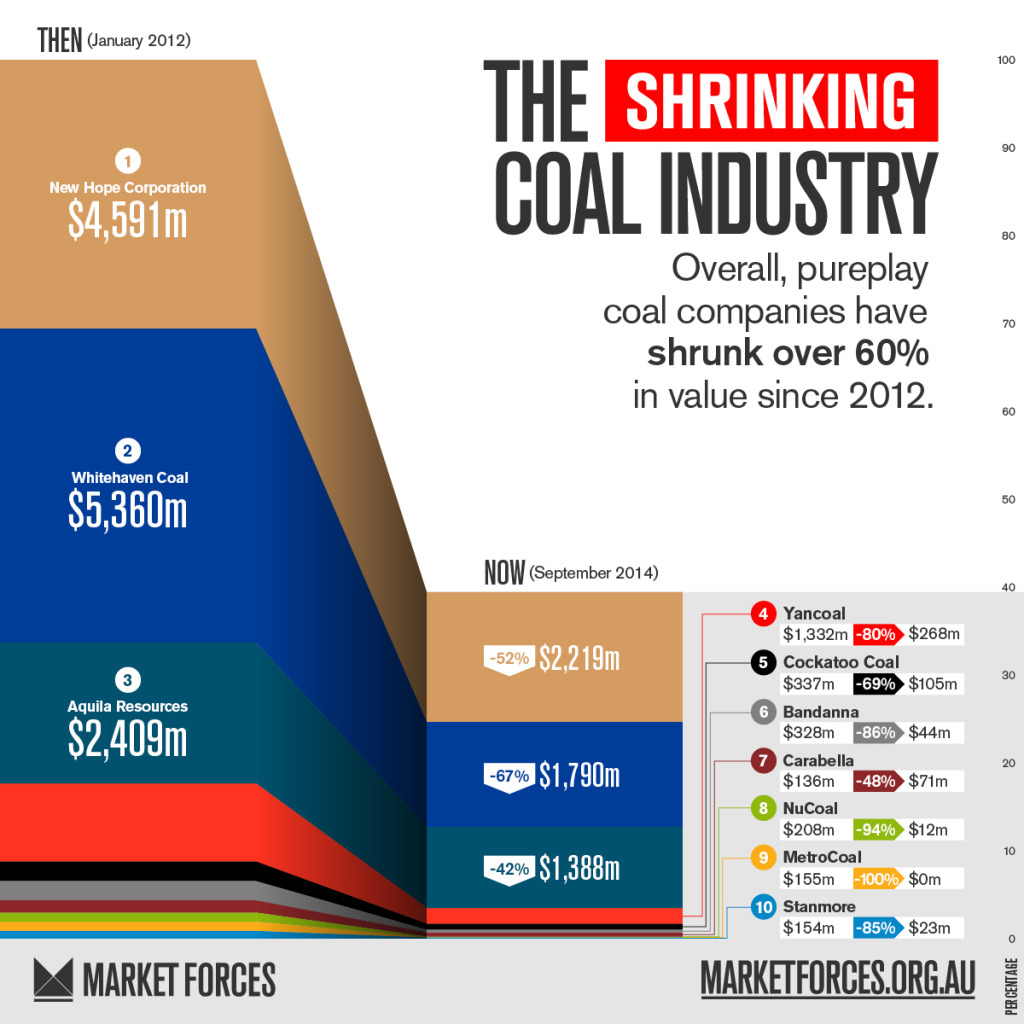

To give a sense of just how much the situation has changed for the coal industry, we looked at the market capitalisation of 10 of Australia’s biggest pure-play coal producers. Here’s how their value has changed since the start of 2012:

Collectively, these companies were worth $15 billion in January 2012 but as of September 2014 were a shadow of their former selves, losing over 60% of their collective worth to be now valued at $5.9 billion.

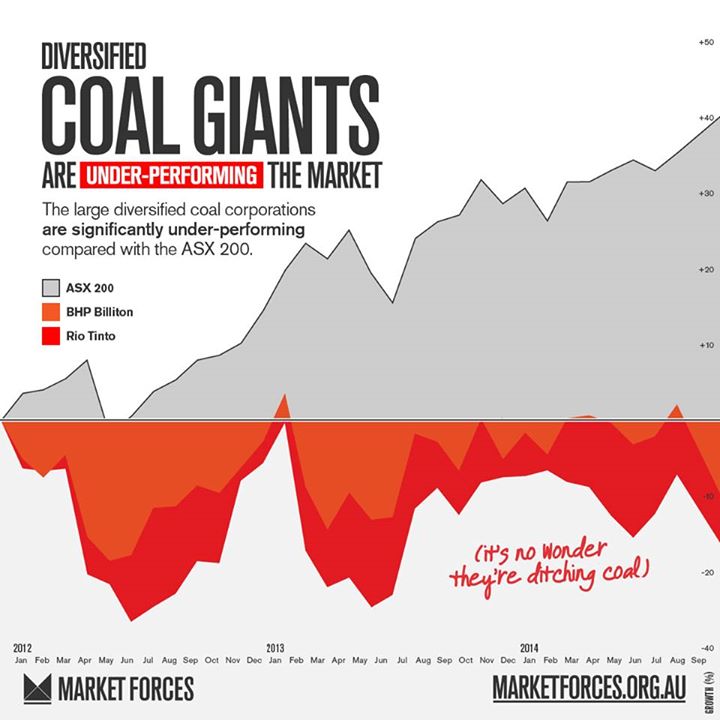

Even the big, diversified miners have struggled. While the ASX 200 has grown 40% since January 2012, both BHP and Rio have underperformed the market, only briefly poking their share prices into relatively positive territory.

Take a look:

While this graph doesn’t in and of itself mean that coal is the cause of BHP and Rio’s failure to keep pace with the market, a look at what both companies are doing gives a sense that coal is the ball and chain dragging them down.

Rio’s Energy CEO Harry Kenyon-Slaney gave a rousing speech at the Australian British Chamber of Commerce in September 2014 where he reaffirmed coal’s central role in energy and wealth creation. But he forgot to tell the audience that Rio had just sold their Mozambique coal assets at a $3.95 billion loss, that they had also sold their Clermont mine in Queensland, sold 30% of their Mongolian coal mining project and put a 29% stake in Coal and Allied, their NSW partnership with Mitsubishi, up for sale.

BHP’s CEO Andrew MacKenzie has publicly defended the role of coal in the world’s energy mix for decades to come, but meanwhile is demerging its thermal coal and other non-core assets into “SpinCo”, having last year reassured BHP shareholders that there are no new major coal projects planned.

The decline in Australian coal companies is not unique. Go to China and the United States and you’ll see the same story, with share prices commonly down 50-70% over the past couple of years. Peabody – whose CEO in August boldly pronounced that “coal always wins out” and that fossil fuels “would be the dominant source of energy for the rest of our lifetimes and beyond” – were recently downgraded to a sell rating by Goldman Sachs on the back of a declining coal price, poor profit results and a rising debt profile.

In fact, this slide shows how Bloomberg’s coal index has dropped by two thirds since 2011 and this drop off a cliff is even more spectacular when compared to the MSCI Global Index, which has grown 50% over the same timeframe.

Source: Bloomberg

So what does the future hold?

The main question for the industry and analysts is whether the decline seen over the last couple of years is cyclical or structural.

It’s pretty easy to tell which camp, Aurizon’s CEO Lance Hockridge, resides. Aurizon is a Queensland-based rail company whose core business is hauling coal. Aurizon has a deal on the table to join Indian conglomerate GVK in their venture to open up the Galilee coal basin. In a recent speech to the Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce, Mr Hockridge justified the deal, which would cost Aurizon about $3 billion, by claiming Chinese coal demand would grow 5% per year to 2020.

Though one wonders how committed to the faith Aurizon can be, when profit has halved due to asset impairments during the year of $317 million – a long list of coal infrastructure assets that have slinked out of financial feasibility… Dudgeon Point, Wiggins Island Stage 2, Surat Basin Rail Joint Venture and Abbot Point T4 have all left the stage.

Unfortunately for Mr Hockridge, recent changes in China’s coal imports and consumption means his 5% growth per year prediction probably looks more accurate with a minus sign ahead of it. Coal production has almost flatlined this year, and with 10 of 34 provinces having pledged to peak coal consumption by 2017, it is not hard to see which way the dust is blowing. The announcement of a ban from 2015 of coal with high ash and sulphur content means has Wood Mackenzie predicting a cut of Australian coal exports to China of 40%. Now there is talk of China re-introducing tariffs that would further chomp into the profit margins of exporters.

For the likes of Aurizon, this all amounts to a multi-billion dollar gamble on a massive new coal project, while the market seems to be pulling up stumps. You’ve got to admire their front!

Let’s face it. Coal is on the slide. Investment analysis predicting structural decline for the industry is piling up, including the likes of Bernstein Research, Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s rating agencies all pointing to a bleak long-term future for coal.

Frankly, for anyone who wants to give the world a fighting chance of avoiding runaway climate change, this is a moment to rejoice. A peak in Chinese and global coal consumption has been on the wish list of campaigners for many years but felt so tragically out of reach. It now appears just around the corner. Now it’s a matter of how quickly the transition from a fossil fuel-based economy to one dominated by renewable energy can take place. It’s going to be a phase of the climate change debate like no other, and one where our political leaders, financial institutions and even ourselves face up to some tough questions.

Questions of political leaders who, in the absence of a vision for an economy beyond coal, offer nothing but false hope to workers over their futures. The reality is that people working in fossil fuels and their families face a tough future and are not being done any favours by politicians who are stuck in a “quarry vision” mentality of the economy. The work done in recent years by environment groups, unions and academic institutions on “just transitions”, promoting the development of new industries to serve the renewable energy powered economy – that work is going to be more important than ever.

Even harder questions will need to be asked of politicians winding back climate policy and steering the economy further and further off course from the global trend away from coal.

Shareholders will need to ask hard questions of companies who would risk their balance sheet and shareholder capital to new, speculative ventures in coal. And questions need to be asked of banks that lend to mines and ports on shaky moral, and economic, foundations.

And for ourselves, the most important question to ask is: is the transformation out of coal and into clean, renewable energy alternatives taking place quick enough to avoid passing a point of no return with global warming? For those of us wanting a safe climate future, the structural decline of coal is one of the most hopeful prospects to emerge in years. And if we’re going to finally get out of this polluting sector, we might as well do it properly.