31 July 2019

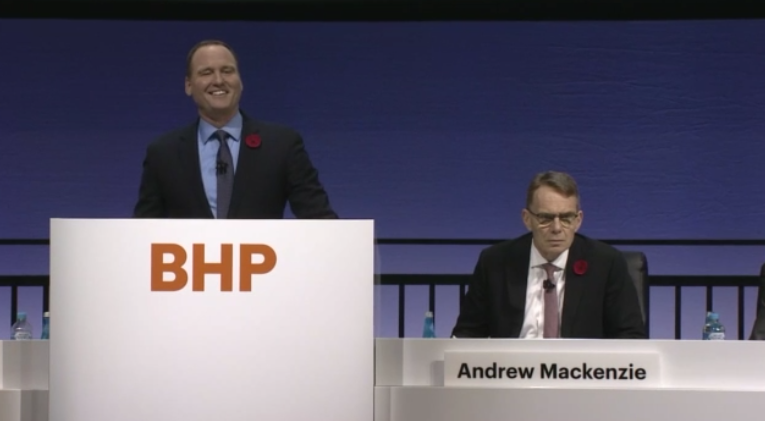

Last week, BHP Billiton CEO Andrew Mackenzie made a speech in London that grabbed global headlines for two main reasons:

- The language he used made it clear that, even if BHP has a long way to go on addressing climate risk, there’s no doubt that the company understands the severity of the problem, and

- Mackenzie said BHP would start to address its “scope 3” greenhouse gas emissions; that is, the emissions produced downstream of BHP’s operations, created as customers use the products that BHP mines.

The speech contained plenty of positives, but also fell short in many areas and definitely left us with more questions. It’s important to note that one of the reasons why the speech played so well for BHP is the context in which the company operates: a sector full of companies and industry lobby groups that still rail against the notion of dealing with their scope 3 emissions and whose stances on climate change action are disturbingly varied.

On the rhetoric

Mackenzie talked in his speech in terms that wouldn’t be out of place at a climate change rally, describing previous events when CO2 was added to the atmosphere even more slowly than the present day and saying:

“These events coincided with mass extinctions and major rises in sea level. And they also suggest that future heating will more likely be towards the upper end of forecasts“

or remarking that:

“the world’s dependence on fossil fuels carries risks with it that could be existential“

or:

“As we have seen from activism and debates from schools to parliaments all around the world, we see this period as an escalation towards a crisis.“

Many would be tempted to dwell on the point that we’re actually already in a climate crisis instead of approaching one, or are definitely facing existential risk as opposed to “may”. But this is the CEO of one of the world’s biggest historical polluters and one of the world’s most influential companies acknowledging the severity of climate change. And that’s more than welcome.

But rhetoric is one thing, and action is what matters most.

Reducing operational emissions

Mackenzie committed BHP to producing science-based, medium-term targets for reducing BHP’s scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions. This contains terms that need clarification.

Medium-term? This means different things to different people so a date needs to be ascribed to it.

“Science-based” is also a term that now carries meaning, as many companies go to the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) for independent verification that targets are aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Whether or not BHP is referring specifically to the SBTi is unclear. If not, a huge question remains about the merits of any “science-based” target the company would define absent credible independent verification that it conforms to the Paris Agreement’s goals.

Scope 3 emissions

Despite BHP making no commitment to materially reduce scope 3 emissions, this is the area that drew most of the attention. Much of the reporting made it look like BHP was setting targets to reduce scope 3 emissions in the same way as its operational emissions, though Mackenzie never pledged to do so. Instead he said BHP would “increase our focus on scope 3 emissions”, and “commit to work with the shippers, processors and users of our products to reduce scope 3 emissions”.

The closest he got to committing BHP to a target was when he said:

“As we have seen from activism and debates from schools to parliaments all around the world, we see this period as an escalation towards a crisis.“

But a ‘public goal’ could be measured by any metric the company considers comfortable and could result in no material change in the amount of scope 3 emissions. Put simply, if BHP had intended to set targets to reduce its scope 3 emissions, it would have lumped this in with its commitments on scope 1 and 2.

Why does this matter so much? Because scope 3 emissions are 97% of BHP’s carbon footprint. They amount to more greenhouse gas emissions per year than Australia produces as an entire country.

So it matters from the perspective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but also for BHP as a climate risk management measure. If we’re to accept, as BHP clearly does, that we need to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, that means BHP’s scope 3 emissions will have to fall as well. It makes sense for BHP to set a target to reduce its scope 3 emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement to minimise the risk the company faces as the world economy decarbonises.

Earlier this year, BHP’s peer Rio Tinto recognised the significant risks posed by its own scope 3 emissions profile, but vehemently opposed a shareholder resolution calling on the company to manage down that risk by setting scope 3 emission reduction targets. Throughout conversations with Market Forces, and in response to shareholder questioning at the company’s AGM, Rio Tinto was unable to provide alternative metrics and targets that would ensure management of the risks posed by the Paris-aligned decarbonisation of the company’s target markets.

BHP’s commitment to “set public goals to address scope 3 emissions” seems an improvement on Rio’s approach. But to demonstrate effective climate risk management, the company must reassure shareholders that its future strategic and capital expenditure decisions will be consistent with the Paris goals. Setting credible Paris-aligned scope 3 emissions targets would provide this reassurance.

Other companies similarly exposed to transitional climate risk through large scope 3 emissions profiles have attempted to shirk any responsibility for managing that risk.

Oil and gas producer Beach Energy’s managing director Matt Kay has stated “scope 3 is probably not a core focus at this point in time; it’s really scope 1 and 2 that our primary focus is on.” Beach’s operational (scope 1 + 2) emissions would be dwarfed by those produced from customers burning its oil and gas. Kay’s comment shows complete disregard for the company’s duty to manage the financial risks posed by a Paris-aligned low carbon transition.

Beach is not alone. Australia’s peak oil and gas body, APPEA, and some of its biggest members – including Santos, Woodside and, interestingly, BHP – have repeatedly pushed back on calls for scope 3 emissions to be regulated. While BHP’s scope 3 commitment is far from perfect, it does show just how far behind other big oil and gas players are on this issue.

$400 million. Enough?

Another feature of Mackenzie’s speech was a Climate Investment Program of US$400 million over five years. Mackenzie said this program was intended to:

“scale-up low emissions technologies that decarbonise our operations. It will drive investment in nature-based solutions and encourage further collective action on scope 3 emissions.“

Most of the commentary and critique was about whether this was a suitable amount of money to invest in emissions reduction. At 1% of the company’s revenue, it’s hard to say that’s a sufficient level of investment, given the war footing path we need to adopt if we’re serious about meeting the substantial economic transformation required to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

But a more important question is: how will the money be spent?

There was no detail on this from BHP and this is another major question that needs to be answered. If BHP can invest $400 million intelligently and leverage the investment for further private sector support towards real climate change solutions, if it can provide the funding that bridges key innovation gaps to accelerate the deployment of clean energy solutions and decarbonised processes for materials production, then it probably has more merit than at first glance. But this is a question only BHP can answer.